Opera House

Opera Stage and Sets

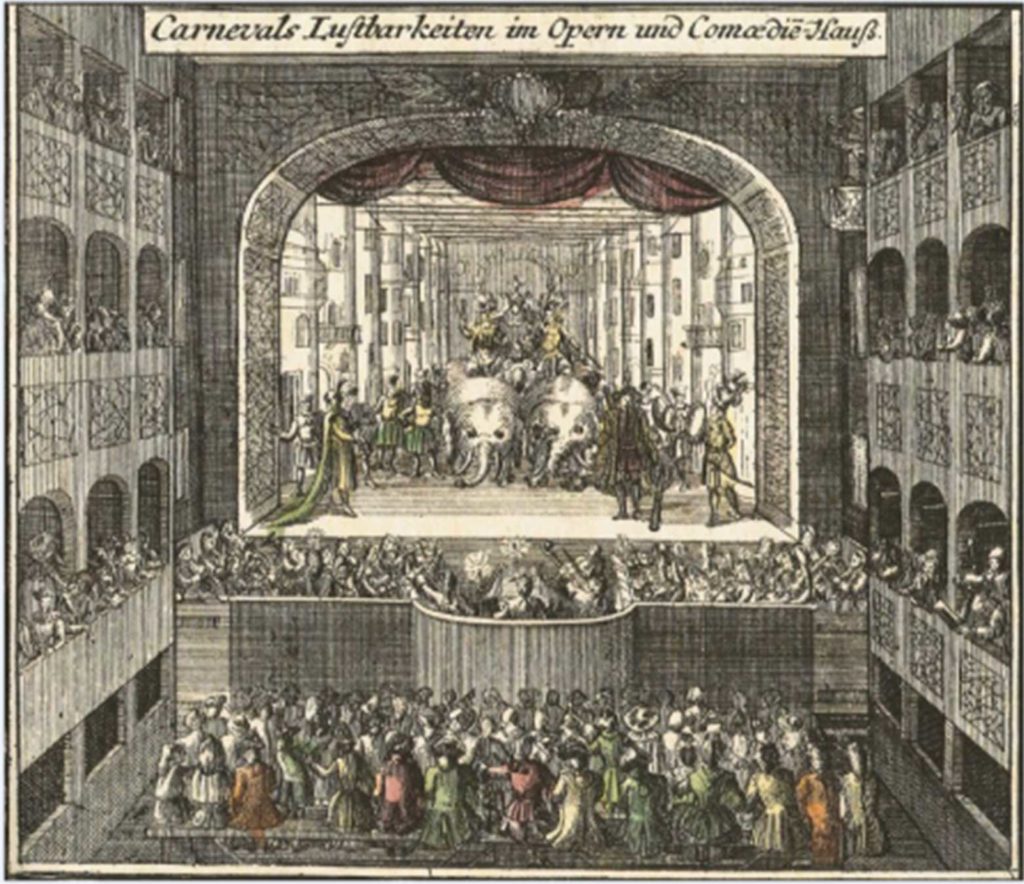

On the stage of the ducal opera, performers could be made to disappear through trapdoors or seemingly fly through the air.

The opera house possessed a large number of sets, pieces of scenery, cloth and cardboard props, and theatrical machines. The costume collection was huge.

Professional musicians such as the famous singer Christiane Pauline Kellner (1664–1745) performed there ¬– as did members of the court nobility and the duke’s own children, who took lessons from the dancing master.

Known as the “Komödiensaal” (Comedy Hall), the opera house was opened in 1685 and transformed Wei¬ssenfels into a centre of the arts with a significance far beyond central Germany. It is documented that around 140 theatrical works were performed there, created by important composers such as Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725) and Reinhard Keisers (1674–1739). But the actual number is thought to be much higher – at least 400.

Remains of wall paintings

In 1753 the Saxon elector donated the theatre to the palace administrator, marking the end of the traditional venue. In 1754 the wooden installations and stage were removed and the space was remodelled for residential purposes. Only a few of the murals remained. They included a fragment of a painting on the stage arch from around 1685 and a decoratively painted window arch from the early eighteenth century.

The visualization shown here is not a complete reconstruction of the former opera house, but attempts to give a rough idea of what it looked like.

The Orchestra Pit: Workplace of Johann Philipp Krieger

The Nuremberg-born composer and organist Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725) served in the court orchestra of Margrave Christian Ernst in Bayreuth and later oversaw the ensemble as court kappelmeister. Afterwards he travelled to Italy and studied the genre of opera in Venice, among other places. In 1677 he was hired as a chamber musician and organist at the court of Duke August of Saxe-Weissenfels in Halle, where he rose to become vice kapellmeister. In 1680 he moved with Duke Johann Adolf I to the newly built Neu-Augustusburg residence in Weissenfels, where he now served as kapellmeister. He created numerous instrumental works and pieces of festive and banquet music for the Weissenfels court and was responsible for the blossoming of opera there. Only a few libretti and musical fragments of his stage works have survived – for example, Der großmütige Scipio Africanus (The Magnanimous Scipio Africanus, 1690) and Der wahrsagende Wunderbrunnen (The Fortune-Telling Miracle Well, 1690).

Aristocratic Audiences

During performances, the court nobility sat on wooden benches in the auditorium. Attendance at the operas put on for the dukes was an obligation and an honour – though not always. On 26 February 1729, when the performance did not get underway until long after 3 am, the noblemen and ladies decided to steal away, leaving the duke behind. He ordered the piece to begin anyway – and then fell asleep. The performance was halted and the duke was taken to bed.

Boxes for the Duke and Duchess

The opera house, which opened in 1685, continued the courtly music culture established by the dukes around 1654 in Halle an der Saale.

The boxes for the duke and duchess were a prominent feature of the auditorium’s architectural design. In 1736 they featured red wall fabric, greenish gold leather wallpaper, and an iron stove – the only heating device in the entire theatre. Guests are said to have dined at semicircular tables in these boxes.

The architectural ornamentation of the boxes is not documented, but we do know that two Hercules figures stood in the theatre in 1754. The visualization shown here recreates the basic spatial structure of the boxes.

Bericht über die Verleihung des Hosenbandordens

Zugang zu den Wein- und Bierkellern

Das Fotopanorama zeigt den Abgang zu den großen Gewölbekellern am Marschallamt im Zustand 2021. Das riesige Vorratslager gliederte sich in “Landweinkeller”, “Bouteillenkeller”, “Langer Keller” im Westflügel und “Frankenweinkeller”, “Ausspeisekeller” (tägliche Ausgabe von Getränken an Berechtigte) sowie “Bierkeller” im Südflügel. Im Nordkeller gab es einen Brunnen.

1736 wird das wohl größte Fass erwähnt: „1 Groß Vaß von 200. Eymbern (rund 13.470 Liter) mit 15 Eißern Reiffen“. Vielleicht ist der im Museum befindliche halbe Fassdeckel mit Herzogswappen ein Teil davon. Die hier zu sehende Ziegelwand stammt aus einer späteren Bauphase des Schlosses, vermutlich aus der Nutzungszeit als preußische Kaserne (19. Jahrhundert).

Fürstliche Hofkellerei

Die Kellerei versorgte die fürstliche Tafel sowie alle durch Hofdienst oder Anstellung berechtigte Personen mit Brot und Getränken („Ausspeise“). Dem Kellermeister unterstand die Lagerwirtschaft für Bier und Wein. Er verwahrte auch die Gläser, Kelche, Schalen und weitere gläserne Tafelgerätschaften.

Die Hofkellerei in Weißenfels bestand aus drei Verwaltungsräumen und den großen Vorratskellern. Zu ihnen führten die Haupttreppe bei der Kellerei und eine zweite am Marschallamt in der Nordwestecke des Schlosses. Die großen Kellergewölbe sind in ihrer Struktur erhalten geblieben.

Princely court kitchen

Silver and Porcelain Chamber

Supervision and care were the domain of special pages. The renowned Prime Minister of the Electorate of Saxony, Heinrich von Brühl (1700-1763), son of the Weissenfels Court Marshal Hanns Moritz Brühl (1665-1727), began his career here as a “silver page”.

Hund Hercules im Tafelgemach

Hund Hercules im Vorgemach

Hund Hercules im Audienzgemach

Hund Hercules in der Retriade

Hund Hercules in der Herzogsloge

Hund Hercules im Schlafzimmer

Hund Hercules im Kirchgemach

Musikbeispiel

Aus: Der Großmütige Scopio (Weißenfels 1690)

(Wolf Matthias Friedrich/Lautten Compagney)

Stairway to the crypt

Musikbeispiel

Aus: Musikalischer Seelen-Friede (Nürnberg 1697)

(Klaus Mertens/Hamburger Ratsmusik)

Hund Hercules in der Gruft

Hund Hercules auf dem Schlosshof

Bereich der ehemaligen Schlossküche

Eine Speiseliste aus der Zeit Herzog Christians

Reception of a high guest

Bericht über den Besuch des Erzherzogs Karl von Österreich bei Herzog Johann Georg von Sachsen-Weissenfels auf Schloss Neu-Augustusburg im Jahre 1703.