The Palace Square / Court of Honour

The Palace as the Seat of Government

The centralization of the state ministries in the princely palace reflected the idea of the absolute state. They included government departments, the financial administration, and school and church authorities. The ground floor of the north wing contained the simply furnished offices of government (the privy council, revenue office, and church council).

The Palace Square/Court of Honour

The inner courtyard was called the Schlossplatz, or Palace Square. It was not paved with cobblestones until 1695 and was used, among other things, for parades by the palace guards and for courtly entertainment. The diversions included performances by tightrope walkers and other acrobats and above all staged hunting events. The first of these events on record was held on the occasion of Prince Christian’s confirmation on 4 March 1682. A total of 122 animals were killed. Beginning in 1699, the courtyard was also used as an arena for fights between wild animals such as bears and wolves. On one such occasion, a bear broke loose and ran into the crowd, but a hunter responded quickly and killed the animal.

The Swiss Gate

Neu-Augustusburg Castle is a stalled building project. Even the journey to the castle indicated this: The approach was from the east. The buildings of the old castle were retained, including the gate area. It was not until 1688/1690 that a new, representative gate was erected with the gallery building. In the west, the new main gate was built at the same time as the front of the new castle, but the associated driveway from the town was not built.

The gate of the west wing was decorated with four larger-than-life statues, possibly personifications of general ruler virtues. It was patrolled by a special guard permitted only to high imperial princes – the Swiss Guard – after which the gate received its name as the “Swiss Gate”. In the understanding of the 17th and 18th centuries, it was located “in front” and was probably the main entrance to the castle.

Gallery and gate

Between 1688 and 1690, a one-storey cross building with a gateway was built at the east of the “Schloss-Platz”. It was based on plans by either Johann Christian Richter, the architect of the Weissenfels Residence Palace, who died in 1667, or the court architect Christoph Pitzler (1657–1707). He had travelled Europe for three years from 1685 onwards on behalf of the Duke, visiting architecture and buildings everywhere.

The Weißenfels Gallery is very similar to the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris. On the one hand, it created the necessary eastern closure for the cour d’honneur; on the other hand, its representative gateway offered the possibility of entering the courtyard in a manner befitting one’s status. In the understanding of the 17th and 18th centuries, this gate was nevertheless “at the back”. In front of the gallery was an area with buildings of the old castle complex, which housed the guard and stables.

The Palace Towers

The palace originally had three towers: the main tower above the central entrance and the towers on the two side wings (one above the palace church, the other above the opera house).

The main tower originally contained only a clock with a bell, but in 1741 a carillon was added. The side of the tower facing the courtyard is decorated with an almost two-metre-high letter “A” with palms. It stands for the founder of Weissenfels Palace, Duke August of Saxony, and the name of the building, Neue Augustusburg. The main tower was destroyed by fire in 1932 and was later rebuilt in a slightly modified form.

The towers on the north and south wings no longer exist today. The south tower was demolished for structural reasons well before 1746. The demolition of the north tower took place in 1819.

Entrance to the Former Office of the Hofmarschall (Today’s Museum)

The Hofmarschall (Lord Chamberlain) was a central figure at every princely court. He was responsible for all organizational matters, and court staff reported to him. In addition, every guest had to register at his office. The dukes of Weissenfels also entrusted such officials with diplomatic duties. Hanns Moritz, father of legendary Saxon prime minister Heinrich von Brühl, served as the ducal Hofmarschall from 1705 to 1714 and as chief Hofmarschall from 1720 on.

Architectural History of the Palace

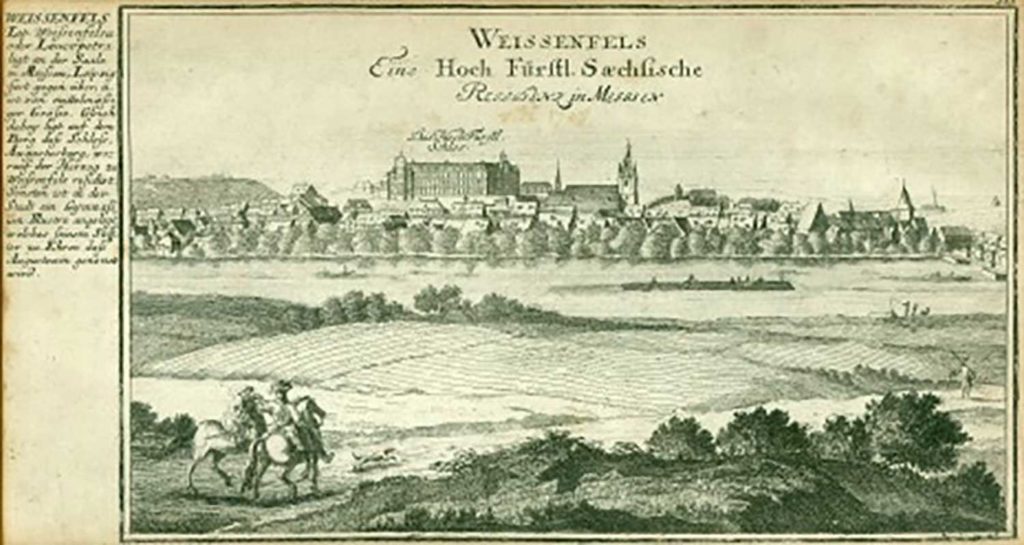

Neu-Augustusburg Palace as we know it today has its origins in the castle complex founded by the ruling dynasty of Saxony around 1185 and destroyed by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years War. There is documentary evidence that in the winter of 1644/45 the massive main tower (the keep) was breached and the residents of Weissenfels were called on to raze most of the remaining complex.

The new residential palace of Duke August (1614–1680), founder of the Saxe-Weissenfels line, was built on the foundation walls of the medieval castle, with work beginning in 1658. The building project was innovative and ambitious for the time: the architect Johann Moritz Richter (1620–1667), a native of Weimar, designed a three-wing early Baroque ensemble modelled on the palace of Weimar. On 24 June 1660, the foundation stone was laid and the palace was named “Neue Augustusburg” in commemoration of the builder and the progenitor of the Saxe-Weissenfels line.

The west and north wings facing the city were the first sections to be built. The north wing contains the palace church, whose foundation stone was laid in 1663. Interior construction began in 1677, and just three years later, the still unfinished building become a ducal residence. Duke August had been granted the right to use the previous residence in Halle for as long as he lived, and his death on 4 June 1680 forced his successor Johann Adolf I to move to the Weissenfels palace with his court. Due to time and money constraints, the new ruler pressed for an end to construction work. As a result, the palace remained unfinished. Ruins from the medieval castle complex to the east were never removed and have survived to the present day.

The palace church was consecrated in early November 1682. The duke’s private chambers were not completed until 1683, those of the duchess not until 1685. Neue-Augustusburg had its own armoury, treasure rooms for silver and porcelain, a court library, and from late 1686 on, a court theatre. It also had spacious apartments for guests (the Elector’s Room, the Gotha Room). Once the crypt was built in 1670, the church contained the dynasty’s burial chamber. The ducal apartments and the stately living rooms were richly furnished with valuable wallpaper, mirrors, chandeliers, silver and wooden furniture, and numerous paintings. Many of the rooms had ornate stucco ceilings; others featured coffered wood ceilings. Some of the hallways, staircases, and rooms were ornamentally painted. Between 1688 and 1690, an elaborate building, the “Gallery”, was built at the eastern end of the palace courtyard.

The palace housed numerous government offices as well as the guard units. It had its own water supply, a large kitchen, a court pastry kitchen, and extensive storage cellars. It also contained a bath for the ducal family. There were built-in toilets hidden in the metre-thick walls throughout the building, and most were accessible from the intermediate staircase landings.

After the death of Duke Johann Adolf I in 1697, the palace’s exterior was largely completed, but the ensemble still contained unfinished or only provisionally furnished rooms, especially in the north wing. Subsequent dukes built numerous courtly buildings in Weissenfels, port facilities on the River Saale, a large riding house, and extensive gardens to the south of the palace, yet construction activities in the palace itself were limited to redesigning individual rooms. The original architectural design, which envisioned a magnificent festive hall and a stately carriage drive to the city, was never fully built.

Between 1780 and 1810, extensive construction work was carried out to structurally secure the sections that were partly in danger of collapsing. Afterwards the south wing was “held together by braces”. In 1815 the palace was converted into barracks for Prussian troops. The Baroque palace church survived, as did the Baroque stucco ceilings in some of the rooms. In 1819 the north tower was demolished, suffering the same fate as the tower in the south wing, which had already been removed for structural reasons.

Beginning in 1820, the Saxon residential palace was called the “Friedrich Wilhelm Barracks”. In 1869 a school for non-commissioned officers moved in; units of the security police (Sicherheitspolizei) followed in 1920. At the end of the Second World War, the palace served temporarily as a refugee shelter.

Between 1956 and 1964, the palace housed a school for local history museums. In 1964 the East German Shoe Museum moved in, marking the start of the building’s development into a museum. Since 1990, extensive work has been carried out to secure and renovate the historical structure. Current plans call for the building to be transformed into an administrative headquarters and a “museum palace”.

The Duchy of Saxe-Weissenfels

The founder of the ruling family of Weissenfels family, Prince August of Saxony (1614–1680), was the second-born son of the Saxon Elector Johann Georg I and his wife Magdalena Sybilla, Electress of Brandenburg.

August’s life was determined by his assumption of the regency of the archbishopric of Magdeburg in his fourteenth year (1628), by the Thirty Years’ War, and by the division of the land that his father ordered in his will in 1652. His father died in 1656, and on 1 May 1657, four special dominions came into being. August’s elder brother, Johann Georg (1613–1680), became the new Elector and head of the family with a residence in Dresden. His three younger brothers August, Christian, and Moritz received parts of Electoral Saxon territory as well as the central German bishoprics. They founded the Electoral Saxon collateral (secondary) lines of Saxe-Weissenfels, Saxe-Merseburg, and Saxe-Zeitz. August resided in the archbishopric of Magdeburg in Halle (Saale) throughout his life. When he died in 1680, the archbishopric became extinct, and the area fell to Electoral Brandenburg. His successor therefore had to leave Halle and move into the newly founded residence in Weissenfels.

The duchy extended along the Saale and Unstrut Rivers and into northern Thuringia and had exclaves around Barby, Jüterbog, and Dahme. In 1663, a special imperial principality (Querfurt) was founded from parts of the Weissenfels territory. In addition to the residence in Weissenfels, important castles were those in Barby, Freyburg (Neuenburg), Sangerhausen, and Wendelstein. They were joined by the Heldrungen and Querfurt fortresses, the prince’s residences in Dahme and Weissensee, as well as the widow’s castle in Langensalza.

The princely families in Halle/Weissenfels, Merseburg, and Zeitz initially grew thanks to numerous descendants. The electors in Dresden, on the other hand, held back considerably with their offspring, probably out of fear of further divisions of the country. It was not until the 1720s that several princes again ensured the continued existence of the electoral family. At this time, the three collateral lines were already in decline due to the lack of male successors: in 1718 the House of Saxe-Zeitz became extinct, followed by Saxe-Merseburg in 1738. In 1746 Saxe-Weissenfels also died out. All possessions reverted to the Saxon Elector.

Although the three princely houses only existed for a relatively short time, their ruling families made enduring contributions to the cultural region of central Germany. Significant works of art, architecture, and intellectual history have preserved their cultural heritage to the present day. The estate of the Weissenfels dukes is largely dispersed. With just a few exceptions it is a treasure awaiting discovery.

Abbildungsnachweise / Musik

Schlosshof: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1, 4, Stich Herzog Christian); Wikimedia (Erzherzog Karl), Neues Archiv für Sächsische Geschichte und Alterthumskunde/Dresden 1893, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Abb. 5/Foto: Elke Estel & Hans-Peter Klut)

Opernhaus: Thüringer Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek (Abb. 1); Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 2); Deutsche Fotothek (Abb. 3); Sächsische Landesbibliothek — Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (Abb. Bühnenbild)

Schlosskirche/Gruft: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig (Abb. 1); Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 2); Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Kupferstich-Kabinett (Abb. 3/Foto: Andreas Diesend); Hamburgische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek/Wikimedia (Abb. 4)

Großer Saal: Monumedia (Abb. 1); Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 2, 4, 5, Gemälde Herzog Christian)

Büchsenkammer: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Rüstkammer (Abb. 1, 2, 6, 7, 8/Foto: Jürgen Lösel, Abb. 3/Fotos: Carola Finkenwirth & Gernot Klatte

Wohngemach des Herzogs: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1, 2);

Schlafgemach des Herzogs: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig (Abb. 1)

Wohnung der Herzogin: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig (Abb. 1); Museum Weißenfels (Portrait Herzogin Louise Christine)

Baugeschichte: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1/Foto: Katharina Vokoun, Abb. 2)

Geschichte des Herzogtums: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1, 2); Joachim Säckl 2003 (Abb. 3)

Audienzgemach: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1,7); Museum Schloss Neuenburg (Abb. 2, 6/Fotos: Jakob Adolphi); Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten (Abb. 3, 4), Schloss Homburg (Abb. 5)

Tafelgemach: Alexander Grychtolik (Video Schäferkantate); Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Neues Grünes Gewölbe (Abb.1)

Großes Antichambre: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig (Abb. 1); Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 2)

Keller: Museum Weißenfels (Abb. 1, 2),

Musik:

Lautten Compagney Berlin (Oper)

cpo Georgsmarienhütte (Kirche)

Sony Music (Tafelgemach)

Imprint

Stadt Weißenfels

Der Oberbürgermeister

Museum Weißenfels im Schloss Neu-Augustusburg

Markt 1

06667 Weißenfels

Gestaltung: Friedrich Lux, Halle/Saale

Visualisierung: Arte4D, Dresden (Modelle: Andreas Hummel & Dr. Tobias Knobelsdorf)

Übersetzung: Adam Blauhut, Berlin

Sprecher: Frederik Beyer, Stuttgart

Panoramafotos: Foto Kind, Weißenfels

Zeichnungen “Hund Hercules”: Bao Han Tran

Wissenschaftliche Beratung Prinzenwohnung: Dr. Bernhard Roosens, Berlin

Gesamtkonzeption: Prof. Dr. Alexander Grychtolik, Weimar,

scriptor rerum, Naumburg (Dipl. Päd. Joachim Säckl)

& Museum Weißenfels

Archivrecherchen: scriptor rerum, Naumburg (Dipl. Päd. Joachim Säckl)

Danksagungen: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Herzog-Anton-Ulrich Museum (Braunschweig), Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten (Potsdam), Arbeitsgemeinschaft Baugeschichte Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha (Dr. Martin Sladeczek, Udo Hopf, Benjamin Rudolf), Udo Hopf, Weimar, Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt (Schloss Neuenburg), Büro für Denkmalpflege und Bauforschung Halle (Maurizio Paul), Heinrich-Schütz-Haus (Weißenfels), Lautten Compagney (Berlin)

Arbeitsstand: April 2022

gefördert von:

Bericht über die Verleihung des Hosenbandordens

Zugang zu den Wein- und Bierkellern

Das Fotopanorama zeigt den Abgang zu den großen Gewölbekellern am Marschallamt im Zustand 2021. Das riesige Vorratslager gliederte sich in “Landweinkeller”, “Bouteillenkeller”, “Langer Keller” im Westflügel und “Frankenweinkeller”, “Ausspeisekeller” (tägliche Ausgabe von Getränken an Berechtigte) sowie “Bierkeller” im Südflügel. Im Nordkeller gab es einen Brunnen.

1736 wird das wohl größte Fass erwähnt: „1 Groß Vaß von 200. Eymbern (rund 13.470 Liter) mit 15 Eißern Reiffen“. Vielleicht ist der im Museum befindliche halbe Fassdeckel mit Herzogswappen ein Teil davon. Die hier zu sehende Ziegelwand stammt aus einer späteren Bauphase des Schlosses, vermutlich aus der Nutzungszeit als preußische Kaserne (19. Jahrhundert).

Fürstliche Hofkellerei

Die Kellerei versorgte die fürstliche Tafel sowie alle durch Hofdienst oder Anstellung berechtigte Personen mit Brot und Getränken („Ausspeise“). Dem Kellermeister unterstand die Lagerwirtschaft für Bier und Wein. Er verwahrte auch die Gläser, Kelche, Schalen und weitere gläserne Tafelgerätschaften.

Die Hofkellerei in Weißenfels bestand aus drei Verwaltungsräumen und den großen Vorratskellern. Zu ihnen führten die Haupttreppe bei der Kellerei und eine zweite am Marschallamt in der Nordwestecke des Schlosses. Die großen Kellergewölbe sind in ihrer Struktur erhalten geblieben.

Princely court kitchen

Silver and Porcelain Chamber

Supervision and care were the domain of special pages. The renowned Prime Minister of the Electorate of Saxony, Heinrich von Brühl (1700-1763), son of the Weissenfels Court Marshal Hanns Moritz Brühl (1665-1727), began his career here as a “silver page”.

Hund Hercules im Tafelgemach

Hund Hercules im Vorgemach

Hund Hercules im Audienzgemach

Hund Hercules in der Retriade

Hund Hercules in der Herzogsloge

Hund Hercules im Schlafzimmer

Hund Hercules im Kirchgemach

Musikbeispiel

Aus: Der Großmütige Scopio (Weißenfels 1690)

(Wolf Matthias Friedrich/Lautten Compagney)

Stairway to the crypt

Musikbeispiel

Aus: Musikalischer Seelen-Friede (Nürnberg 1697)

(Klaus Mertens/Hamburger Ratsmusik)

Hund Hercules in der Gruft

Hund Hercules auf dem Schlosshof

Bereich der ehemaligen Schlossküche

Eine Speiseliste aus der Zeit Herzog Christians

Reception of a high guest

Bericht über den Besuch des Erzherzogs Karl von Österreich bei Herzog Johann Georg von Sachsen-Weissenfels auf Schloss Neu-Augustusburg im Jahre 1703.